By Jyoti Thottam and Amantha Perera - The International Crisis Group, an international human rights group based in Brussels, released an alarming report on Tuesday, timed to coincide with the first anniversary of the end of Sri Lanka's civil war. The report, "War Crimes in Sri Lanka," calls for an international inquiry into violations by Sri Lankan security forces, describing several incidents in which civilian targets, including hospitals and humanitarian aid shelters, were shelled.

The group also claims to have evidence suggesting that civilian casualties in the last months of the war were much higher than earlier estimates: "The period of January to May 2009 saw tens of thousands of Tamil civilian men, women, children and the elderly killed, countless more wounded," the report said. The Sri Lankan Army defeated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, an ethnic Tamil separatist group, after 26 years of conflict. May 18, 2009, marked the official end of the war, when the LTTE leader, Velupillai Prabhakaran, was killed.

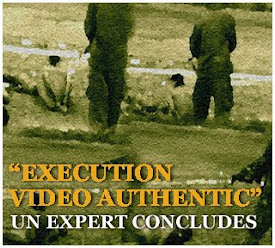

The ICG report is the latest of numerous efforts by human rights groups, governments and international agencies to hold the Sri Lankan government accountable for the way it conducted the last phase of the war. The report stops short of actually revealing any of the evidence, which the ICG says will be given only to "authorities that are able to ensure a credible legal process that includes the protection of witnesses." But it does provide a chilling, comprehensive account of the many already published allegations against the Sri Lankan government. They include a video apparently showing soldiers executing blindfolded Tamil men; the alleged battlefield execution of two LTTE leaders who had surrendered with their families and staff; and the shelling by security forces of a U.N. aid distribution center within a no-fire zone, resulting in 11 civilian deaths.

The government of Sri Lanka, however, remains as defiant as ever. It has so far faced no legal action or international sanction, and this report is unlikely to change its refusal to allow any international investigation into alleged human rights abuses or war crimes. How has a small, trade-dependent island nation withstood this pressure? Sri Lanka's president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, has made refusal to bow to international criticism a crucial part of his image as a tough leader. A recent article in the Indian Defence Review listed this as one of the central principles of Rajapaksa's military strategy: "telling the international community to 'go to hell.'"

Rajapaksa has done so, in perhaps less colorful language, on several occasions. When the United Nations Human Rights Council considered calling for a similar investigation last May, shortly after the war ended, Sri Lanka's allies — including China, Pakistan and India — rallied against the measure. Instead, the HRC passed a resolution praising Sri Lanka's success in ending the war. Billboards in Colombo trumpeted that bureaucratic finesse in Geneva as another victory for the nation. A similar effort within the U.N. Security Council failed.

The ICG report acknowledges that neither of those two bodies are likely to take any action, and instead calls on U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon to use his authority to start his own inquiry. But Rajapaksa has already sidelined Ban. When the Secretary General announced plans in March 2010 to set up an advisory committee on Sri Lanka, Rajapaksa said such action was "unwarranted and uncalled for", as no such action had been taken against other U.N. members facing similar criticism.

Rajapaksa's overwhelming election victories this year have strengthened his hand, and he is unlikely to feel any internal pressure to allow an international inquiry. He won the January presidential election by a 1.8 million-vote majority and his coalition secured 144 of 225 seats in the April parliamentary elections, just shy of a two-thirds majority. "The responsibility of a sovereign government is to the people who elected it," says Keheliya Rambukwella, a minister in Rajapaksa's government. "The vast majority of people have shown that they trust the President and his administration."

He has made some token steps toward reconciliation. Since the new government took office in April, it has relaxed certain emergency regulations. Rajapaksa also pardoned the Tamil journalist and editor Jayaprakash Tissainayagam, who had been sentenced to 20 years imprisonment for receiving funding from the Tigers. Tissainayagam's conviction had been widely criticized as an attempt to silence criticism of the government. This week, Rajapaksa appointed his own eight-member expert commission to look into the conduct of the war.

The United States still has some leverage. It is Sri Lanka's largest trading partner, and it may have jurisdiction to investigate two prominent names in the ICG report: Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the president's brother, who is a U.S. citizen, and former Army Chief Sarath Fonseka, who is a green-card holder. Both were questioned by U.S. officials last year, resulting in no action other than a minor diplomatic controversy. The story isn't quite over yet, however. The U.S. ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues will submit his report on Sri Lanka on June 16.

© TIME

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3e80e84d-5e62-4b32-80e5-40f4817da15a)

No comments:

Post a Comment