By Professor Mark P. Whitaker - To begin with I want to thank Mr. Arun Gananathan and Mr. Uvindu Kurukulasuriya and the Tamil Legal Advocacy Project for inviting me to speak at this Sivaram Memorial Event.

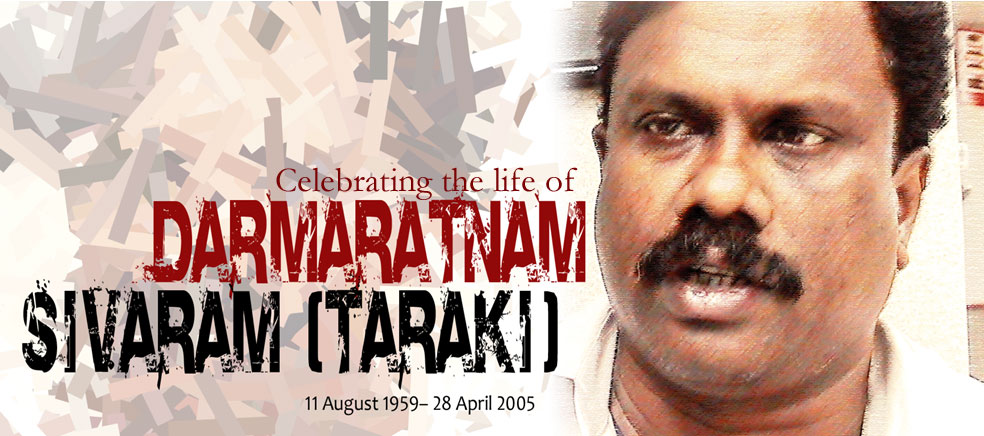

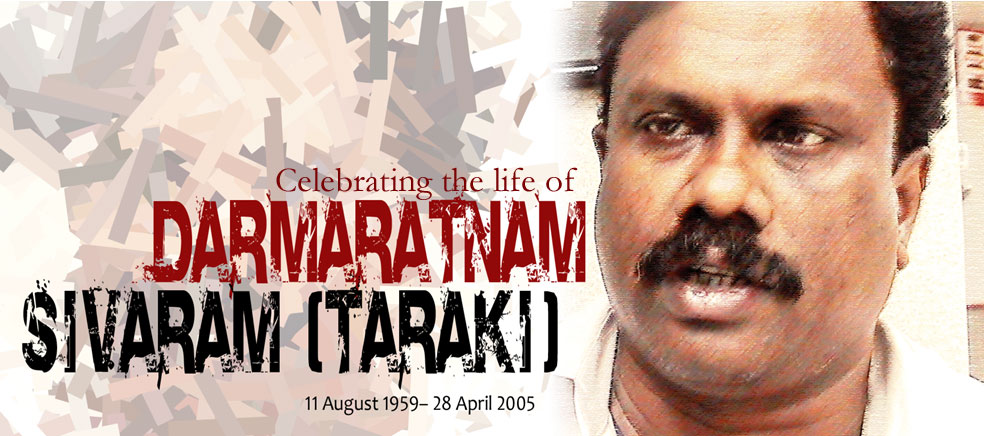

It is entirely fitting and proper, I think, that a memorial for Sivaram should also entail public remembrance of the many Sri Lankans of all ethnicities who, like him, have sacrificed their homes, their freedoms, and, in all too many cases, their lives as journalists. Their sacrifices bespeak the intense need to protect freedom of speech as a fundamental right not only in Sri Lanka but in any state proclaiming itself a democracy. Now it is exactly five years since April 28, 2005, the night Sivaram Dharmeratnam -- one of Sri Lanka’s most original, important, and (obviously, to some) infuriating journalists -- was abducted on a Colombo street and, as we soon learned afterwards, murdered.

Since I was unable to attend his funeral and actually see that, yes, the impossible had happened and my friend of over twenty years was now dead, I long felt a nagging, ridiculous suspicion that it was not true. That another late night phone call would come, another impossible knock on the door, and his inimitable voice would say again, “Ah, Mr. Whitaker, what have you been up to, machchaang .” I knew, of course, that this was not the case. His cousin called and told me, immediately after the funeral, that he had touched Sivaram’s surprisingly cold face in the casket. I knew he was indeed gone. But knowing is one thing; understanding quite another; and so a chance, periodically, to grieve for my friend officially is to me still very helpful.

But then, of course, I know there is a larger purpose here that makes this mourning also a kind of necessary civic education. For Sivaram’s death was not, like some sepia photograph of an old atrocity, a singular event in a fading history. From 1992 to 2009 the Committee to Protect Journalists estimates that 18 journalists were killed (by all sides) because of what they wrote or said during Sri Lanka’s long civil war . And if we cast our historical net wider yet to trawl from, say, 1983 to 1992, a period including the Sri Lankan government’s anti-JVP war, then we haul in a far higher number of journalist-victims including, for example, the famously photogenic Rupavahini news anchor Richard de Zoysa, Sivaram’s old friend and mentor, and the very man that drew Sivaram into journalism. (Not long after his abduction, de Zoysa’s body was found washed up on the Moratuwa coast. Sivaram had to identify the remains). The majority of those killed, of course, were Tamil; but others, such as Lasantha Wicrematunga, the late editor of The Sunday Leader, were not. And many other journalists, Tamil, Muslim, and Sinhalese, also clearly due to the war, were forced into exile or, most famously in the case of the J.S. Tissainayagam, jailed (though we can all be thankful for his release on January 13, 2010). Apologists for these actions have often pointed to the harsh necessities of war for their excuse. But as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have both recently noted, the end of the war between the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE last May has not meant an end to the violent harassment of journalists . The unsolved disappearance of the political analyst Prageeth Eknaligoda on January 24, 2010 during coverage of the recent elections is but one bitter example among others of its continuance. Sadly, then, the practice of using violence to suppress journalism has, now, a long history in Sri Lanka, and seems to have become unmoored recently even from the martial circumstances originally used to justify it. It has become a kind of tradition – or, worse, a kind of routine, like tea in the morning: very sour tea.

None of this, of course, would have surprised Sivaram. One of his foremost traits as a thinker was his ability to comprehend unsentimentally the key role violence often plays in the politics of states, especially his own. He was never shocked, thus, at the notion that his journalism might make him a target; he simply tried – and for years succeeded – in being an especially difficult target. Similarly, Sivaram never viewed the mistreatment of the press in Sri Lanka as something either unique or disconnected from the world at large. He was always very careful to place Sri Lanka’s political foibles in a wider context of global forces and well distributed international ‘security’ practices. More amazing to me, however, in retrospect, is how anyone who viewed the world and his own mortal fragility within it, as he did, with such brutal clarity could nonetheless blithely carry on being a journalist in Sri Lanka. And I feel a similar amazement, and admiration, for those journalists who have come after Sivaram, risking what he risked, and all too often, ending as he ended. What explains such persistence?

Thinking of all this, I find my mind drawn back fifteen years ago to 1995, the first time Sivaram visited America, and the first time he told me that he thought his journalism was going to get him killed . Sivaram had come to America that year on an exchange program sponsored by the U.S. Information Agency. At that time, the USIA had such programs to spread ‘democratic’ and ‘pluralistic’ values to important journalists they had selected from the world’s inter-ethnic hot spots, a purpose Sivaram found more amusing than helpful given that his visit coincided with America’s burgeoning O.J.Simpson hysteria and the racial tensions revealed therein. In any case, this “Building Democracy in Diverse Communities” program brought Sivaram to Washington D.C. on September 14, 1995, and from there, over the course of three weeks, to Los Angeles California, Akron Ohio, Miami Florida, and eventually back to Washington D.C. From there, Sivaram was supposed to return immediately to Sri Lanka on October 12 – “Have a safe and pleasant journey!” chirped his overly chatty USIA Travel Schedule -- but with his six month, multiple-entry visa in hand he flew down to visit me instead.

He arrived in Aiken, South Carolina, where I teach, wearing a natty gray sports coat, rolling a single small suitcase, and toting a large plastic carrying-bag full of pamphlets on democracy and grass-roots political action which he gleefully deposited in my trash can since, as he put it, “they appear to have all been written by giddy insects.” But he told me, nonetheless, that he liked his first look at America and Americans. “You are such a happy, naive people. It’s been really very pleasant, machchaang, like looking at children playing. Very cheering.” He was especially cheered by Aiken’s local supermarkets, which, in those pre-Keels supermarket days, he found ridiculous in their fecundity. He liked being taken to the Wal-Mart Supercenter so he could stand in one of the food aisles and simply laugh. “I could kill myself eating here, machchaang. I could easily murder myself.” After my wife, who was teaching in California at the time, arrived for the Thanksgiving holidays, we took Sivaram to Charleston, South Carolina’s tourist city, and the very place where the American Civil War started. It was partly for pleasure, of course, but partly for Sivaram’s own research, for while Sivaram was thoroughly enjoying his first trip out of South Asia, his journalistic curiosity was fully engaged. He was forever striking up conversations, buttonholing, and generally chatting up strangers; and not the tame people USIA had paraded before him in their ‘workshops’. Rather, in every city he visited, Sivaram had slipped out, and walked around, seeking the poor and the angry and the marginalized. By the time he got to me in Aiken he had spoken with Ethiopian political refugees in Washington DC, Mexican laborers in several states, a prominent Chinese-American dissident in LA, several black labor activists there too, a Marxist priest in Miami (with whom he had, one evening, sipped wine on Biscayne Bay while talking about the Haitian boat people disaster), and unorganized low wage workers everywhere – none of whom were on his official itinerary. He simply had an ear for those voices others do not hear. So it was in Charleston, walking down Meeting Street with Ann and I, when Sivaram noticed a picket line in front of the Omni Hotel and shopping arcade. He immediately joined it, asking questions, striking up conversations, eventually finding out the whole story behind the strike. In about an hour he knew more about the labor politics of South Carolina than I had learned in several years. Buying a local paper, he pointed out that the whole event was simply not covered. “And your USIA people, my friend, think they have a free press.”

And he laughed.

At various times, during that first long visit, I had to take him to dinner parties with other academics. These were invariably a disaster. We would go and there would be wine and cheese and attempts at witty talk over discretely sipped goblets of expensive wine. If the academics were older or especially self-important they would then attempt to lecture Sivaram on what they thought he should know about the world, politics, philosophy, and literature. Since Sivaram was generally better read than they were, and his experiences more concrete, these were intensely uncomfortable moments, made worse by Sivaram’s penchant for subtly – and sometimes not so subtlety --baiting such people. I remember once a young fancily degreed academic attempting to explain Kojeve’s writing on Hegal to Sivaram, only to stand dumbfounded and stone-faced as Sivaram, after pointing out how profoundly mistaken this young man was in his interpretation of Kojeve, proceeded to quote, from memory, the relevant passages. Sivaram was particularly, loudly, and rudely hard on academics who thought of themselves as ‘politically active’, maintaining, with a dismissive wave of his wine glass, that the only true sign of political activism in an academic was a death threat and imminent imprisonment. “You have to risk something. Otherwise you are just playing,” he would say. He ended the evening, as he often did such occasions, by laughing at the selection of tasteful ‘eastern’ music, the under spiced food, the ersatz antique ‘Third world’ paraphernalia on the walls, and the politics. He also ostentatiously drank too much, and let it show, something which he rarely did unless he wanted to. After we left, I was furious.

“Couldn’t you have been more polite? For God’s sake!”

“Machchaang, machchaang, don’t upset yourself. They will think nothing of it.”

“Come on! They’re not completely naive!”

“No, Mark, you are wrong. They are all completely naïve.”

On the way home from one of these affairs, I forget which one, Sivaram looked longingly on the moonlight silvering the oak trees flashing by and said that he hoped when he died that his molecules would mingle with the soil of the Batticaloa district so that, in this way, he would eventually become one with its jungles and flowers.

“Why are we talking about death?” I asked, still somewhat testy about the disastrous party.

“Because, young man, what I am doing now is eventually going to get me killed. It has to.”

We argued about this and he ended up telling me that when he died I would know it because a bottle of arrack would arrive in the mail. “I’ve put it in my will”, he said.

“Unless you would prefer something else. Should it be a bottle of gin?”

“Arrack is fine. But you are not going to die.”

“Oh I am going to die, young man. Just remember the arrack.”

In the event, when he was killed, I heard by phone call and not by post. Over the next several weeks, as his death sank in, people kept calling me – his friends, his journalistic colleagues, academics -- all offering theories about who might have killed him. Nobody knew exactly anything, of course, and we still don’t, though we all shared suspicions that are probably accurate. But I know why people kept calling. For to work on solving the mystery of his death was, at least, to be doing something like what he would have done. It was a kind of final tribute, an acted memorial, completely fitting, and still going on in the actions of his endangerd journalistic peers. The day after his murder, however, as I sat down to drink a glass of arrack and ginger, the arrack taken from the last bottle I purchased with him – at the Cargills in Dehiwala, as it happens – I began to think not about who killed him but why he was killed. Or, rather, as he was intimating to me fifteen years ago, why he had to be killed by someone, eventually. And the answer I came up with is that he was simply too good at his job. He refused to withhold his insights, or cloak them in diplomatically vague abstractions. He believed, instead, in being perfectly clear, in letting everyone know, in making sure all those left out were included in, even if this meant he had to painstakingly teach them what ‘in’ looked like. He was, in short, far too blatantly Sivaram.

Consider, for example, the kinds of judgments, insights, and principles Sivaram brought to his work as Taraki and as an editor for Tamilnet. Let me, in fact, enumerate some of them.

First, Sivaram was one of the few journalists who understood early on how profoundly the end of the Cold War had transformed Sri Lanka’s geopolitical circumstances. This was something he had remarked upon on as early as 1990, long before other commentators were taking this tectonic shift into account; and it gave him an insight into the complex politics being played out between India, the US, the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government that, I suspect, was embarrassing in its clarity for all the players involved. Second, Sivaram from 1990 onwards wrote with insight and sympathy about the problems of east coast Muslims and upcountry Tamils, the excluded of the excluded. This unusual insight enabled him to note without surprise the kinds of spanners their particular problems frequently threw into the works of proposed political settlements and strategies by all sides. I do not imagine this pleased overmuch those in love with false and simplistic clarities. Third, Sivaram had a thorough understanding of the role violence plays in the running of modern nation states -- even supposedly peaceful ones. With this knowledge Sivaram was able to show how, for example, the then current Sri Lankan state was in fact dependent upon its oppression of Tamil people; and to argue, hence, that any settlement would have required not only a radical restructuring of the state, but an equally radical reordering of the means of violence currently at its disposal. I can’t imagine how threatening this notion must have been to those in charge of the guns and shackles, but I can guess. Fourth, Sivaram had practical experiences as both a warrior and a politician. This is because, unlike many intellectuals who participated in the Tamil nationalist movements of the eighties, Sivaram was equally active in both the military and political wings of PLOTE, his organization then. The practical consequence of this was his ability to understand and explain both the political and military aspects of Sri Lanka’s complex situation equally well -- a fact of no small chagrin, I would guess, to politicians wishing to be hazy about military fiascos, or to militarists too much in love with force for force’s sake. Fifth, Sivaram was willing and able to talk with anyone. Moreover, his electric personality was such that most people, regardless of political stripe, were willing to talk to him as well. It should be borne in mind that many of his most prominent public mourners in Sri Lanka, for example, were Sinhalese journalists, some of them quite Chauvanist in their attitudes, and a number of whom eventually labored under death threats on his behalf, and went on to suffer similar fates for covering other stories displeasing to those in charge. This ability to talk to all sides in Sri Lanka, and occasionally to provide a span of insight between them, was not just a shallow conviviality over drinks but the deep undergirding of his journalism: he left no one out of his conversation, and he made sure you knew it in his writing. I’m sure this rankled his killers and would-be killers no end. Sixth, Sivaram was the consummate journalistic professional. What he meant by ‘professional’ is, of course, a pretty complicated business to explain, since his beliefs about this ranged from the deeply political (‘professional’ meant you could not hide, even on pain of death, from the implications of what you thought were right) to the deeply practical (never write anything unless you had checked and double checked the facts). But Sivaram’s professionalism, nonetheless, will perhaps be his greatest contribution to South Asian journalism. When he died, I could hear the painful creaking of spines stiffening all over the region, and all over the world. And clearly, given the journalistic body count, this has lasted. Finally, seventh, there is Sivaram’s fierce and unrelenting dedication to what he perceived as his ultimate goal: achieving due rights and justice for all the Tamil people. Although he was astutely adjustable and strategic when it came to discussing how this goal might be achieved, he never hid his disdain for anyone who thought it appropriate to aim for something less. For him it was worth his own death, worth taunting his enemies with his refusal to leave or temporize, and, finally, worth a kind of resolution for his molecules as they mingle with the soil of the Batticaloa he so loved. “I find this idea strangely comforting,” he once said to me, ten, or fifteen or twenty years ago, about this eventual recycling. “I will bloom with the flowers.”

And then he laughed.

So I think I know why he was killed. But they killed him, of course, for their purposes, far too late.

As for what his death has meant to me? I remember talking with one of his close cousins on the phone soon after Sivaram died. He told me that, although he felt selfish saying so, what troubled him most about Sivaram’s death were the conversations he now would never have with anyone else like Sivaram again. For Sivaram, he claimed, could talk about ideas with him in a way no one else could. I knew exactly what he meant. I think all those who knew him well do. When he died, that died – that kind of talking, that flash of brilliance, that fierce irony, and fearless thinking. He made us all uncomfortable in the most valuable way. What a legacy to be carrying on with.

Thank You.

The full text of the speech delivered on April 29, 2010 by Professor Mark P. Whitaker at a meeting held in London to mark the 5th death anniversary of slain journalist Darmaratnam Sivaram (Taraki). The event was organized by Friends of Sivaram and Tamil Legal Advocacy Project. Mark P. Whitaker is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of South Carolina, Aiken, where he also holds an endowed chair in Social and Behavioral Science. He is a cultural anthropologist, and has conducted research in and on Sri Lanka since 1981. Most of his research has focused on politics, religion, and journalism in Sri Lanka’s Tamil community. He is the author of two books: Amiable Incoherence: Manipulating Histories and Modernities in a Batticaloa Hindu Temple (1998), the University of Amsterdam Press; and Learning Politics from Sivaram: The Life and Death of a Revolutionary Tamil Journalist in Sri Lanka (2007), Pluto Press. He has also written 17 articles. He met Sivaram Dharmeratnam in 1982, shortly after arriving in the Batticaloa district to begin fieldwork, and the two of them remained close friends and intellectual colleagues till Sivaram’s death on April 28, 2005.

Notes:

1. Sivaram liked to pronounce the word 'machchaan' (male [cross] cousin) as 'machchaang.' Note: in the interest of avoiding transliteration problems, I am showing long vowels by doubling letters.

2. “18 Journalists Killed in Sri Lanka since 1992/Motive Confirmed”, Committee to Protect Journalists [www.cpj.org/killed/asia/sri-lanka/] accessed 16/4/10.

3. “Sri Lanka: Demand Investigation into missing journalist” Urgent Action, ASA 37/003/2010 [www.amnesty.org/en/region/sri-lanka] accessed on 4/16/10; “Sri Lanka: end Harassment, Attacks on Journalists”, Human Rights Watch [www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/01/29/sri-lanka-end-harrassment-attacks-journalists] accessed 16/4/10.

4. The following story is drawn from my book. See Whitaker, Mark. (2007) Learning Politics from Sivaram: The Life and Death of a Revolutionary Tamil Journalist in Sri Lanka, pp. 113-116. London: Pluto Press.

Friday, April 30, 2010

Remembering Sivaram Dharmeratnam

Friday, April 30, 2010

Sri Lanka war continues by other means

Vino Kanapathipillai / Editor, Tamil Guardian - I would like to thank the Tamil Legal Advocacy Project for inviting me to speak here today.

Most of us are here today not only because of a connection to Sivaram, but also because we are engaged, in one form or another, in Sri Lanka’s protracted and deepening ethnic crisis.

In the next few minutes, I’d like to make some observations on Sri Lanka today, drawing on an analytical approach favoured by Sivaram. In other words, always seeing events as inevitably situated in long running trends and processes.

The conventional understanding of Sri Lanka is that after the military defeat of the Liberation Tigers last May, the country is in a post-war or post-conflict scenario. In this understanding, the path to peace is one defined by reconstruction, development, reconciliation and so on.

However, this is based on a very narrow understanding of war, as merely the clash of arms. Wars end when armed clashes end. In fact, the clash of arms is a manifestation of vehemently contradictory politics that have already been underway.

To quote Carl von Clausewitz, one of the theorists Sivaram was most influenced by, “war is a continuation of politics by other means.”

In this logic, even the most casual observer of the Sri Lankan state’s conduct can see that the situation today is the continuation of war by other means.

By war, I am referring to the systematic and ideologically coherent practices of the state against the Tamils and other non-Sinhalese. What we see today is the intensification of structural violence against the Tamil people that began from independence.

By violence I do not mean just disappearances, abductions, murders, rapes and torture, although these are continuing, as we know. I mean more the structural practices of the state, aimed at limiting and suppressing the thriving of non-Sinhala people. We are familiar with some of these: colonization, erasing of Tamil usage in state practices, and the efforts to limit and destroy the socio-economic possibilities for Tamils.

None of this is new. It is part of efforts of the Sri Lankan state, since independence, to break down all resistance to the Sinhala national project. What is this project? To turn Sri Lanka into a modern day realization of an ancient myth that the island belongs to the Sinhalese and in which the minorities have a subordinate existence. As such, anyone who stands in the way of Sinhala majoritarianism – including principled Sinhalese who are not supportive of that project – are destroyed. This, as we know, is also why Sivaram was killed.

The recent parliamentary elections in Sri Lanka have once again brought to power the southern party that most aggressively espouses a Sinhala majoritarian view. It is a case of history repeating itself. It is a carbon copy of the 1956 elections. Then, as now, as the Tamils sought a political arrangement between Tamils and Sinhalese, the Sinhalese voted into power a party that vehemently rejected any compromise with the Tamils.

While constitutional changes are almost certainly in the near future, as the President’s party almost has the required two thirds majority, only the blindest of optimists see these changes as possibly positive towards addressing even basic Tamil grievances. Those who suggest this do so with no regards to either the historic evolution of the Sri Lankan state or the contemporary realities of Sinhala power today.

Let us be clear, change in Sri Lanka cannot come from within.

The last elections prove how overwhelmingly the structural bases of power serve Sinhala nationalism. The JVP for example lost several seats purely because its core platforms of Sinhala nationalism and anti-market economics were more convincingly taken up by the UPFA and President Rajapaksa.

In a contest between the UNP and the SLFP – both of which are essentially Sinhalese entities despite the token Tamils – the party that more aggressively pursued the Sinhala national project has won convincingly.

What we see now is another phase in the further entrenching of the Sinhala people’s dominance over the non-Sinhala.

It is not merely a question of human rights abuses, or lack of media freedom, or lack of governance. Rather, it is a specific kind of governance. This is why the Sinhala people – as in 1956 – are with Rajapaksa and his party.

To repeat, the core driver of Sri Lankan politics continues to be this Sinhala majoritatian nationalism.

This mass ideology predates independence and has now been entrenched in the mechanisms of the state. It is now carried forward in the state bureaucracy, the composition, practices and strategies of the military, the directing of international aid and state investment to some places and not others, and so on.

This Sinhala majoritarianism remains the central obstacle to the constitutional recognition of the Tamils, and other Tamil speaking peoples, as having a rightful place, equal to the Sinhalese, on the island.

And until it is confronted and checked, a truly democratic and peaceful Sri Lanka, one which treats all communities as equal, will remain an impossible dream.

It is worth noting that the ascendancy of this Sinhala majoritarianism has taken place while the country has been in the close embrace of the international community. After several decades of ‘engagement’ by the liberal West there still isn’t a hairsbreadth of liberal space in Sri Lanka. Indeed, it can be argued that Sri Lanka has headed successfully in the opposite direction.

Thus the war continues in Sri Lanka through politics. And as long as the war continues, there will be resistance. Some of us focus on media freedom, others are more driven by human rights concerns, or the humanitarian or developmental needs of the oppressed. But unless all of us recognize that the problems we are opposing stem from a strategic logic embedded in the state, we cannot succeed in our objectives.

We do not believe the course of Sinhala majoritarianism will change from within. Every effort by the Tamils to negotiate or reason with this majoritarianism has resulted in further violence. Look at the history of constitutional change since independence, for example.

Sri Lanka today is in a state of flux. As the Sinhala-dominated and supported state continues to wage war on the Tamil speaking communities, various forms of resistance will emerge, not only from within, but also from without. Today, the Tamils problem is being assessed and reflected upon in far more spaces across the world than ever before in our history.

I have of course not forgotten that we are here today to mark the fifth anniversary of the Sri Lankan state’s murder of Sivaram. In closing, I would like to say a few words about him.

The Tamil Guardian has had a relation with Sivaram almost since it began. He was instructor and mentor to the longer-serving volunteers on the paper. He taught us not only how to write, but how to think through the complexities of politics; to go beyond a surface analysis of a problem and explore the underlying structural movements. For this we are grateful.

As long as the oppression of Tamils continues, so too must the struggle for Tamil rights. Most of us knew Sivaram through our engagement in this struggle. I think it behooves us all to continue to remain committed, in whatever field we are in, to continue his resistance.

Thank you

The full text of the speech delivered on April 29, 2010 by Ms. Vinothini Kanapathipillai at a meeting held in London to mark the 5th death anniversary of slain journalist Darmaratnam Sivaram (Taraki). The event was organized by Friends of Sivaram and Tamil Legal Advocacy Project.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=46e7d772-bcc8-47b6-b46e-526d5f878d99)

Friday, April 30, 2010

Sri Lanka: Delegation of Pakistan National Defence University meets Secretary Defence

A delegation of senior military officers of Pakistan Army, Navy and Air Force from National Defence University (NDU) of Pakistan, on study tour to Sri Lanka,s paid a courtesy call on Secretary Defence Gotabaya Rajapaksa this afternoon, 30 April.

A discussion was held between Secretary Defence and Pakistani Defence Delegation on security challenges both in Sri Lanka and Pakistan during this meeting. The defence delegation of Pakistan National Defence University arrived at the country on 26th April for a study tour in Sri Lanka scheduled to be departure on 1st of May.

© Defence.lk

Friday, April 30, 2010

Indo - Sri Lanka Maritime Issues: Challenges and Responses

By Commodore R. S. Vasan - The long and hard fought war between the LTTE and the SL forces came to an end on 19th May 2009 with the killing of the LTTE Chief Prabhakaran. The nearly three decade war from Eelam I to Eelam IV fought at different intervals claimed over 1, 00,000 lives. The final phases of war did bring out various issues related to the way the war was concluded in the Island. It is alleged that many war crimes were committed that need investigation. While the reasons for the defeat have been discussed and analysed, it is clear that the progressive loss of sea control by the LTTE, the inability to replenish war materials due to sinking of over a dozen LTTE merchant ships and stricter maritime border control were instrumental in the weakening of the LTTE as a reckonable maritime terrorist force at sea.

There were also other causes such as the proscription of the LTTE by over 33 nations. That led to stricter monitoring of the financial and material transactions of all terror groups. The Global War on Terror (GWOT) launched by USA post 9/11 had many components and initiatives that tightened the noose around the LTTE’s neck. Karuna’s breaking away from the LTTE and joining hands with the Government led forces gave the SL Army a rare insight in to the mind of the Guerilla force and enabled it to prevent surprises which had in the past given spectacular results for the LTTE.

Elections: Both the Presidential and the Parliamentary elections were held which have strengthened the hands of Mahinda Rajapaksa. The show of solidarity (by certain sections including the Tamils) with the beleaguered Army chief who led the SL Army to victory did not translate in to votes when Sanath Fonseka decided to contest the elections. The Tamils who feared that they would now be governed by majoritarianism discriminatory policies that would subjugate the aspirations of both Muslim and Tamil minorities.

IDPs: While many announcements and promises were made soon after the war about the relocation of the Internally Displaced Persons with in 180 days, the ground situation was not conducive both due to the demining effort and also the process of screening for LTTE cadres. In addition there were also suspicions that the President sought to change the demography of the North and the North East by raising additional army units and positioning them in the reclaimed areas. This was seen as a move to prevent another united move by the minority Tamils to return to armed struggle at some future date.

This paper is an attempt to examine the contours of Indo-Sri Lanka maritime issues post the defeat of the LTTE and the possible impact on safety and security in the sub continent. Various developments have taken place since the defeat of the LTTE. The notable ones are discussed in the succeeding paragraphs.

Augmentation of Armed and Para military forces: SL did not lose much time to raise its own Coast Guard while simultaneously planning to increase its Army strength by 1.00.000 cadres. As far as the Coast Guard creation is concerned, the situation could be compared to what happened in India in 1976 when then empowered committee felt the need for a Coast Guard to be raised for peace time tasks of preventing poaching, smuggling, fisheries protection, EEZ Patrol, Search and Rescue, Maritime Pollution etc., The Sri Lanka which has closely interacted with the Indian Navy and the Indian Coast Guard realized the importance of having a Coast Guard that could be tasked more cost effectively during peace time. It has taken considerable time for the Indian Coast Guard to come of age and it is expected that the SL Coast Guard likewise would go through the learning curve before becoming a credible force.

The experience of many Eelam wars has brought out the need for ensuring that the seas surrounding the Island are not used for anti national activities. With the defeat of the LTTE the Palk Bay would again witness resumption of increased fishing activity. The possibility of the fishermen from the two countries becoming involved in some of the age old practices of smuggling /drug peddling can not be ruled out. In addition, while the refugee influx is not as high as it was there is still a considerable section of the Sri Lankans Tamil in Tamil Nadu. There are reports of reverse illegal entry to Sri Lanka by many of the Refugees who are checking out the ground situation themselves.

Energy Issues: Sri Lanka imports all its energy needs and therefore is keen to invest in offshore drilling and exploration in the Mannar basin. The initiative gained momentum after India discovered gas and oil in the Cauvery basin. Even when Sri Lanka was engaged in the war against LTTE, it was trying to balance Chinese and Indian interests in off shore exploration in the Mannar basin. Of the five blocks identified the bid for block 001 was won by Cairn India Limited and on July 07, 2008 the Government of Sri Lanka, through the Minister of Petroleum and Petroleum Resources Development signed a Petroleum Resources Agreement with Cairn Lanka (Private) Limited. The exploratory and drilling activity is expected to start in April 2010. China has also been offered a block to develop with out any bidding showing the special status being given to China in the critical energy sector.

Natural Disasters: The enormous havoc caused by Tsunami on both Indian and Sri Lanka coast has brought to fore the importance of being prepared to meet such contingencies in future. Indian Navy was the first to reach out to its neighbours including Sri Lanka. The role of Indian Navy which cleared the approaches to Galle harbour was highly appreciated by Sri Lanka. The geographical proximity of a regional power should be a matter of great comfort to Sri Lanka which should join hands with Indian Navy and the Coast Guard to have contingencies in place and rehearse them.

Fisheries: There was total ban on fishing when the SL Navy was engaged in various operations against the LTTE. Notwithstanding this situation, the Indian fishermen continued to fish in troubled waters by crossing over to Sri Lankan waters. With the removal of the LTTE from the scene, the fishermen on either side of the IMBL are coming into conflict over fishing issues. Many fishing vessels have been apprehended by both the Indian and Sri Lankan Maritime security agencies due to increasing intrusion on both sides. With this pattern, more and more clashes at sea and arrests can be expected. The ban on fishing which is enforced from April 15th for about 6to 8 weeks again brings in additional problems for the administration. Also the mechanized vessels which are banned from trawling close to coast routinely indulge in violating the rules in unmonitored areas leading to clashes between groups of fishermen.

The waters around Kachchativu continue to interest the Indian fishermen who fish there due to increased yield and variety. They have not pardoned the Central and the State Governments for ceding this Island in 1974. Many studies have been conducted and many out of the box suggestions have been made to declare the Palk bay waters as waters of common heritage. However, the proposal is yet to be accepted by both sides. With the continued insistence on historical rights of the Tamil fishermen from Ramnad district the crossing of IMBL and fishing around Kachchativu continues much to the consternation of both the countries.

After the conflict, for the first time Indian fishermen attended the Annual Feast of St. Anthony’s church, at the Kachchativu Island on February 27 and 28 this year. The feast was attended by both Indian and Sri Lankan fishermen and devotees. Indian Coast Guard and the Sri Lanka Navy coordinated the event. A total of 3387 Indian fishermen and devotees left Rameshwaram in 114 boats on February 27. Local devotees numbering 824 also participated in the feast. It is thus expected that the old practice of holding the annual festival on the Island with participation by both the sides would be now restored. This would also ensure that the Navy and the Coast Guard would be engaged on both sides in ensuring that there are no untoward incidents and safety of the pilgrims is ensured during the passage to the Island

Economic Developments and Investments in Sri Lanka: Many nations around the world are taking interest in the Island nation due to the strategic location of this small Island country. Sri Lanka straddles the Indian Ocean and overlooks the Sea Lines of Communication. Any facility in Sri Lanka that is likely to be made available at a future data would be of great importance to China which is looking for presence in IOR. Other countries likewise have realized the importance of the Indian Ocean which in addition to having the busiest Sea Lines of Communication has become an arena of power play with the shifting of power centers to the Asia Pacific region. The list below and the map indicating the locations of such investment is indicative of the economic assistance being provided to Sri Lanka on lucrative soft loans/aid.

a) Post war - Hong Kong-based conglomerate Huichen Investment Holdings Ltd. investing $28 million to develop SEZ located in Mirigama, 55 km (34 miles) from Colombo port and 40 km from the international airport.

b) Hambantota Port Development Project (worth US$1 billion)

c) Norochcholai Coal Power Plant Project (worth US$855 million)

d) Colombo-Katunayake Expressway (worth US$248.2 million)

e) 2006 to 2008, Chinese aid to Sri Lanka grew fivefold, replacing Japan as Sri Lanka’s largest donor.

f) Interest free loans, subsidised loans

g) Australian assistance for setting up coastal security monitoring network.

It is clear that the economic investments in the infrastructure while benefiting Sri Lanka would also provide the required leverages for the investing nations who expect not just economic returns but also strategic gains in geo strategic terms. India and China which are two raising powers in Asia are seen to be in competition for strategic space in the IOR.

Strategic Power Play in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean Region.

A lot has been written and said about the Chinese overtures in the Indian Ocean. The map above is illustrative of the Chinese ambitions which at the moment just have economic connotations. However, it is clear that these are strategic long term investments with an eye for the future. The decision at one level is driven by compulsions of protecting the seaborne trade of China and the energy routes. At another level it is about engaging the neighbours of India to check mate India on the classic principle of ‘engage the neighbour of your prospective competitor’.

In addition just as many nations around the world who were compelled to deploy their naval vessels for patrolling in the Somalian waters, the Chinese also started deploying their war vessels in the troubled waters infested with Piracy. The map below is indicative of the piracy attacks in the region that has forced both India and China to deploy their naval units. Commencing end of 2008, PLA Navy has commenced marinating an anti piracy patrol in the Gulf of Aden and off the east African coast. The process of deploying PLA Navy units in the Indian Ocean Region has also provided invaluable operational and environmental inputs to the Chinese who would be better prepared to meet the emerging challenges of Piracy and Maritime Terrorism in areas of interest.

This power play has been going on for some decades now with both the countries trying to woo the Indian Ocean Littoral states with investments and concessional loans for development. Sri Lanka has gained from this power rivalry both during the war as well as during the post war period. It is not a secret that Sri Lanka used the China card in India and would have had no reservation about using the India card in China and Pakistan to obtain what ever it wanted for furthering its war efforts. Sri Lanka obtained military assistance from China, India, Pakistan, Iran, Israel, South Africa and other western countries including US.

While there are many areas of investment from the Chinese two strategic investments hold particular interest for analysts. The first is Hambanthota port and the second one is the modern airport that is coming up not far from this port. A lot has been discussed about the Hambanthota deep water port. According to reports, India lost an opportunity to build this port due to bureaucratic bungling at the top echelons in the Government. The details of the two projects are contained subsequently.

The deep water of Hambanthota which is expected to be thrice the size of Colombo port doubtlessly would provide the economic impetus to the southern part of Sri Lanka. The Chinese would definitely would look forward to being provided with turn round facilities for the PLA Navy units that would be routinely deployed in the Indian Ocean Region.

The Chairman, Dr. Priyath Bandu Wickrama of Sri Lanka Ports had this to say about the future potential of this strategic port.

“Over 200 ships sail this route [daily] and we want to attract them… Our vision is to consolidate the position of Sri Lanka as the premier maritime logistic centre of the Asian region”

While Hambanthota Port that is coming up in the South with Chinese assistance has generated lot of interest and debate, not many have realized the importance of the airport that is also being built with Chinese assistance close to the deep water port. The airport is being built at a cost of about US$ 210 million. The details are as under:-

1. Extent of land -2000 hectares

2. Initial construction covers an extent of 800 hectares.

3. Aerodrome design: Designed to meet the ICAO specification for code 4F.

4. Runway Length: 3,500 metres in length with a width of 75 metres.

5. Taxiways: 60 metre long taxiway from the runway centre line to the edge of the apron.

6. Apron: 10 parking positions initially with the total being 80.

Air Field Capacity: Annual Service Volume of the aerodrome at short and medium/long term planning horizons will be 30,000 and 60,000 movements respectively.

7. Terminal and related buildings: Proposed 10,000 square metres to accommodate 800 peak hours and 100 domestic passengers both ways

Implications: On completion of Hambanthota and the airport, it does not take an expert to conclude that it would provide a direct aerial route to a southern outpost of strategic importance in Sri Lanka. Initially designed as a Cargo handling airport would allow China to commence operating direct flights to this airport. This would provide strategic air lift capability and logistic support to PLA ships that may stage through Hambanthota. It is natural for the PLA ships to call on Hambanthota while on passage to and from Gulf of Aden. This would be crucial for supporting the Chinese IOR missions both in peace and during times of hostility. In essence, the completion of Mattala airport would provide the aerial bridge to the southern areas of Sri Lanka including the strategic deep water port of Hambanthota.

In addition this factor should also be viewed in the backdrop of the bids made by Sri Lanka to host the Common Wealth Games (CWG) in 2018. The deep water port and the nearby airport would put Hambanthota on the world map if this bid comes through. It would also enable the SL Government to augment infrastructure in the undeveloped portions of Southern Sri Lanka.

While commenting on the relations of Sri Lanka with the two major Asian powers, Jayantha Dhanapala a Sri Lankan diplomat observed “This is not a zero sum game where our relationship with China is at the expense of our relationship with India. We cleverly balanced the relationship.’

Options for India: This paper would not be complete unless certain options for India are discussed. India would need to change the ways in which it deals with Sri Lanka particularly in the post LTTE period. The defeat of LTTE has given a lot more freedom to Mahinda in terms of his ability to manoeuvre in the new world order.

India has to increase economic engagement and cooperation in defence/offshore exploration and fisheries. The proximity of India would make it easier for India to invest heavily as the bids for most projects could be with in its reach. It is tougher though not impossible for China to invest in many areas in competitive bids. India would need to consciously develop counters to China’s presence by constant engagement and by remaining competitive.

Increased investment in Education, IT, Health and defence cooperation would be easier with the core competence in these areas. Officers and other ranks from Sri Lanka are being routinely trained in India at all levels. There is excellent cooperation amongst the uniformed personnel on both sides. There is a need to allocate additional vacancies and increase the intake of the trainees at all levels. This would enable the Sri Lankan military personnel to imbibe the training and operational ethos of the Indian Armed Forces and also bring about greater cohesion in common areas of interest.

The historical and cultural linkages would remain for ever and this is an area for further engagement by enhancing people to people contact. Indians contribute the maximum in terms of tourist traffic to the Island. There is plenty of scope for increasing mutual visits for eco tourism and religious tourism in both the countries.

Conclusions: In the light of the discussions above the following conclusions could be drawn:-

1. With the geo strategic importance of Sri Lanka it would attract greater attention of the global powers particulary post the LTTE defeat.

2. China would continue to capitalize on the opportunities for assisting Sri Lanka in infrastructure development with an eye for future IOR ambitions. These investments particularly in ports/Airports/transport sector by China are expected to increase the leverage of China vis-à-vis India. The availability of funds and the decision making process in China makes it easier for quick decisions to be taken to develop China’s interests in Sri Lanka.

3. Issues of fishing in mutual EEZ and in Palk Bay will continue to add tensions and would engage the law enforcement agencies, politicians and NGOs for a long time till imaginative suggestions and practical solutions acceptable to both sides are put to practice.

4. Political developments as of now are not being received favourably by the Tamil citizens who now feel the heat as a minority subjected to majoritarianism. Both Sri Lanka and India would need to work together to ensure that this feeling of alienation is addressed and corrective visible measures initiated.

5. Sri Lanka would derive many benefits from the fierce competition for space and maritime influence in IOR not just from China and India, but also from others who would engage themselves in both economic and strategic partnerships of varying dimensions. While there are no doubts that it would benefit Sri Lanka, the Island country has to guard against being manipulated in the super power or regional power rivalry.

6. India perhaps would continue to be uncomfortable with the increased Chinese presence and influence. India would need to shed its colonial hang over and get on with serious restructuring in its engagement policies vis-à-vis Sri Lanka. Unless it is ready to engage in equal measure and also change its archaic procedures in decision making, it would lose out to external players resulting in erosion of its clout.

7. India would need to engage Sri Lanka in a constructive manner to retain its strategic advantage.

Commodore R. S. Vasan is presently the Head, Strategy and Security Studies at the Center for Asia Studies at Chennai. This Paper was presented at a National Seminar at Chennai on Ethnic Reconciliation Economic Reconstruction and National Building in Sri Lanka organised jointly by Center for Asia Studies and the Indian Centre for South Asian Studies on 12-13Apr 2010. The author is presently Head, Strategy and Security Studies at the Center for Asia Studies, a think tank located in Chennai.

© South Asian Analysis Group

Friday, April 30, 2010

An indicator of what comes next for Sri Lanka's media

By Bob Dietz/Asia Program Coordinator - In Sri Lanka, there is a lull of sorts in outright attacks on the media as the Rajapaksa government takes stock of where it stands, which is in a very strong position: Last May the government declared a final victory in the brutal 30-year conflict with Tamil secessionists. In January, President Mahinda Rajapksa won a convincing victory in the presidential elections, and in April, his United Peoples Freedom Alliance took 144 seats of the 225 member seats in parliamentary elections, with a chance to build a political coalition that will give him the two-thirds majority he needs to begin rewriting the constitution.

The country’s media remain as partisan as ever, though some outlets have accepted that the Rajapaksa family has won, and have started to trim their anti-government stance. Others remain adamant in their opposition.

There was recently an indicator of what might come next for the media. The president appointed former Labor Minister Mervyn Silva to be his deputy minister of media and information. Silva’s appointment was confirmed by parliament on April 23.

We’ve written before about Silva, and it wasn’t very encouraging. In March 2008, we complained in a letter to the president about an incident in which state television employees reported a spate of attacks that began after many were involved in a much-publicized on-air dispute in December 2007 with then-Labor Minister Silva. He had shown up at the station with a group of men to complain that the station hadn't covered one of his speeches. Five staff members reported being stabbed, beaten, or slashed with razor blades by unidentified men, according to The Associated Press.

And an update on another case: The wife of a missing journalist took matters into her own hands on April 22, and hand-delivered letters to all the new members arriving in parliament. Sandhya Eknaligoda wanted them to take action on her husband Prageeth’s disappearance. Police tried to stop her, but she managed to get her letters into the MPs’ hands. There is still no explanation for what has happened to her husband, a columnist and cartoonist for Lanka e News. Eknaligoda has been missing since January 24.

© Committee to Protect Journalists

Friday, April 30, 2010

Sri Lanka: Ready For Business

Interviewed by Megha Bahree - The Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Ajith Navard Cabraal, is responsible for the monetary policy of his war-torn country. He's 55 years old, likes jazz and classical music, and doesn't eat fish because he has them as pets. He stopped in New York after the recent International Monetary Fund meeting in Washington, D.C. and spoke with Forbes' about reducing inflation, liberalizing the economy, and investment opportunities in Sri Lanka now that the 26-year war is finally over.

Forbes: What are you doing to put the economic fundamentals in place now that the war is finally over?

Ajith Nirvad Cabraal: Inflation is down from a high of 28.6% in June 2008 to 3-4% last year. We're taking a prudent approach and going forward we will keep a close tab on it. We didn't allow the [Sri Lankan] rupee to depreciate and we targeted reserve money strongly. Even the IMF told us that we were [perhaps] too strong but we wanted to get into shape quickly. One problem was high food prices and 2.5 years ago we took a fairly significant decision to double our paddy crop. Sixty percent of the population is in rural areas so we took care of the farmers and shifted income of 54 billion rupees ($475 million) from urban to rural [pockets]. Rice prices are down now [after initially going up in urban areas] because of higher yields.

Are you noticing any changes in the economy, or is it still too soon?

We can already see that the prices of fish and rice have gone down by 30% and 20% [respectively]. By the end of the conflict we were importing 80% of our milk and now that's reduced to 60%. All these are signs of development. The peace dividend is being absorbed by those who have suffered. There is $6 billion worth of work currently in progress, to improve the roads, the port, a new international airport is being built, new coal and hydro power plants are under construction. All of this had already set a stimulus rolling.

Where are the business opportunities?

Tourism is the biggest opportunity. On that front we have performed far less than our potential. We have ancient cities, beautiful beaches, great wildlife, but the conflict hindered all of that. We have a target of [attracting] 2.5 million tourists over the next three to four years. The change in the overall climate has had a good impact and there can be an increase in the production of tea, rubber and the apparel industries.

Are you doing anything specifically in the north, where the fighting was concentrated?

Traditionally people in the north have been farmers and fishermen. There has been an increase in demand of credit for boats, motors, agricultural implements and we are focusing on that.

Is there a plan to privatize the assets and the businesses held by your government?

The government has a fairly significant ownership, which will not be sold. Let the private sector compete. Government-owned banks are competing with private and foreign banks. If you take the banks here, it was the government that bailed them out with huge support schemes and the private sector policy had to depend on the government to rescue it. Moreover, people voted in favor of not selling. The other party campaigned on a platform of privatization and it lost. [That said,] there are plenty of private sector investments available. Anyone is free to set up a new conglomerate; there is no need to buy a government company to do that. The private sector will also be a good test for government institutions as they will have to compete as well. There are no special deals for the government sector.

From when do you know President Mahinda Rajapaksa?

I've known him since we were in college. He was studying law and I was studying accounting. Politics and economics go together. A long term economic agenda, if you attempt to implement it without political backing, it will fail. We have consciously done that Sri Lanka. We targeted reserve money and interest rates and these hurt the government tremendously. But I had convinced the president that it's essential to have long-term vision. He does and that's very comforting to me.

There's a power shift taking place in South Asia. Where do you think Sri Lanka is headed?

The Chinese have a strong appetite for infrastructure development and have projects of about $1 billion; the Malaysians are in the telecom sector; the Indians are in the road and rail sector with about $300-$400 million; American hedge funds have an appetite for government paper and Treasury bills and bonds of about $1.5 billion; the sovereign bonds have attracted about $700 million. People shouldn't have much concern if India or China enter Sri Lanka because if you look at the whole picture there are others as well.

© Forbes

This site is best viewed with firefox

Search

Is this evidence of 'war crimes' in Sri Lanka?

Archive

- ▼ 2010 (1312)

- ► 2011 (687)

Links

- Reporters Sans Frontières

- Media Legal Defence Initiative

- International Press Institute

- International News Safety Institute

- International Media Support

- International Freedom of Expression eXchange

- International Federation of Journalists

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Asian Human Rights Commission

- Amnesty International

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=2912bb6b-6a9f-4bf2-bc55-bfbcafa5b663)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6830228f-4faf-474f-89b3-0a07718e093a)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=dd6de341-b924-41bd-9afa-cc2ced5139e0)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5044ab1d-c631-479d-9318-efc7e802ca62)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=893ed85c-728f-4bc3-9a9f-7de1716f73f8)