By Sudha Ramachandran | Asia Times

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

This means that Rajapaksa, the first beneficiary of the amendment, need not go into retirement when his current second-term ends in 2016 - he can remain president for as long as he wishes, subject to re-election.

Given the manner in which incumbent presidents in Sri Lanka, including Rajapaksa, have used state machinery during polls to ensure re-election, it does seem that Rajapaksa will remain president for life. In fact, the 18th amendment also enables the president to appoint a person of his choice to head the Election Commission. "With the Election Commission now in his pocket, he can ensure re-election with margins of his choice forever," a Colombo University professor told Asia Times Online.

Sri Lanka's constitution, which came into effect in 1978, provides for an executive presidency. It vests enormous powers in the president. In fact, it is believed that Sri Lanka has the most powerful executive presidency in the world.

By its very definition, an executive presidency is anti-democratic. In Sri Lanka, it has been more so, as checks and balances have been steadily whittled away, enabling successive presidents to function in an authoritarian manner. This has prompted calls for abolition of the executive presidency.

Indeed, all presidential contenders in the past two decades have pledged to abolish the executive presidency, only to forget the promise once they were in the president's seat. The fact that successive governments did not enjoy the required two-thirds majority in parliament to amend the constitution provided a useful excuse for not abolishing the executive presidency.

This was not a problem that Rajapaksa had. Earlier this year, the ruling coalition scored a massive victory in general elections. While it was just a few seats short of the two-thirds majority required for constitutional amendment, this did not pose a problem as it was able to easily ensure defections from the opposition. The 18th amendment bill sailed through parliament with support from several opposition members.

Instead of abolishing the executive presidency, the Rajapaksa government used its huge majority in parliament to do the exact opposite. It has brought in a constitutional amendment that further empowers an already powerful president.

The 17th amendment, which was passed in 2001, aimed at curtailing presidential powers. Under the amendment, residential appointments of superior judges, attorney general and auditor general, heads of independent commissions such as the election commission, the human-rights commission, and the bribery and corruption commission, required the approval of a Constitutional Council.

No such approval will be required henceforth. The 18th amendment replaces the Constitutional Council with a Parliamentary Council whose "observations" (not approval) will be sought by the president in making these key appointments.

This means that the president can henceforth appoint loyalists to these independent commissions. It will politicize every democratic institution in Sri Lanka and remove the last remaining checks and balances on the president. It has serious implications for the fairness of future elections.

Rajapaksa is hugely popular among the island's Sinhalese majority, especially since the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and the end of the civil war in May 2009. Accorded god-like status by his supporters, Rajapaksa won a second term as president earlier this year. His grip over power was further enhanced with the landslide victory of the ruling coalition in parliamentary polls in April.

In an article in the Sri Lankan Daily Mirror, Rohan Samarajiva points to an interesting feature of Sri Lankan presidential elections since the introduction of the executive presidency - no incumbent president has ever been defeated. That is, a sitting president who has sought a second term has never been defeated. This is largely because presidents have brazenly misused state machinery to their benefit during elections. Put simply they have controlled the campaign, the vote and its outcome.

Limits on the number of terms a president can seek are found in most countries with a powerful presidential system, the logic behind this being that "absence of change in an office in which power is so concentrated is a recipe for abuse of power and possible dictatorship", analyst Jehan Perera writes.

A Colombo University professor told Asia Times Online that "removing restrictions on the number of terms is not terribly wrong by itself if it were not for the fact that it is hard, if not impossible, to get rid of an incumbent president in Sri Lanka". Speaking on condition of anonymity, the professor pointed out that with the 18th amendment removing the last checks on the president's powers, the country had now become "a constitutionally sanctioned autocracy".

Proponents of the constitutional amendment have justified it on the grounds that these changes are required to ensure political stability and economic development. But perpetuating Rajapaksa’s rule is more likely the motivation.

Besides being president and the commander-in-chief of the country's armed forces, Rajapaksa is minister of defense, finance and planning, ports and aviation, and highways. In all, he is directly responsible for 78 institutions.

The president is not the only Rajapaksa in a powerful position. His brothers hold important posts too. Gotabhaya is the defense secretary. He is in charge of the three wings of the military, as well as the coast guard, the police and intelligence. Immigration, a major revenue-earner in labor-exporting Sri Lanka, urban development and land reclamation too fall under his purview.

Another brother, Basil, who is an elected member of parliament, is the minister of economic development and a senior presidential adviser with oversight of wildlife conservation, and investment and tourism promotion boards. He is the head of task force for reconstruction of the war-ravaged northeast and the special envoy to India. Elder brother Chamal is the speaker of parliament. Chamal's son Shashindra is the chief minister of Uva province. Mahinda's son, Namal, is already a political powerhouse though this is his first term as a member of parliament.

The Sunday Leader noted some months ago that Sri Lanka "seems to have reached a point of one-family rule. Every aspect of our lives from the registry of our births, to the taxes we pay ... and the documents we must carry in order to move freely is under the control of Rajapaksas. Their domination is absolute."

The establishment of the Rajapaksa raj in Sri Lanka is, however, not the work of the Rajapaksas alone. A feeble opposition has enabled it. Ranil Wickremesinghe, the leader of the main opposition party, the United National Party has led it through a string of electoral defeats. Yet he remains at the helm, steering the party towards oblivion.

The only person who was able somewhat to challenge the president was his former army chief, Lieutenant General Sarat Fonseka. That challenge has been snuffed out. Fonseka, now a member of parliament, has been sentenced by court martial to a dishonorable discharge and is to be stripped of his rank and medals. He faces another court martial too. Defense Secretary Gotabhaya told BBC's Hard Talk that the government would hang him.

The president can be impeached by parliament. That requires a two-thirds vote in favor of impeachment, an unlikely prospect in the near future. What is more, in the unlikely event of an impeachment motion, the president can count on more than a little help from his brother Chamal, the speaker.

Sixty-four-year old Rajapaksa is in good health. With a subservient parliament, judiciary, Election Commission etc; no opposition to speak of and civil society and media silenced, he is firmly in the saddle. Thanks to the 18th amendment, he seems set to remain at the helm for life.

Sudha Ramachandran is an independent journalist/researcher based in Bangalore.

© Asia Times

Friday, September 10, 2010

Sri Lanka: Rajapaksa looks to his new era

Friday, September 10, 2010

'Threats against exiled journalist’s family in Sri Lanka must cease' says IFJ

Press Release | International Federation of Journalists

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

“The IFJ calls on the Sri Lankan authorities to identify those responsible for threats against Pushpakumara’s wife, Waruni Balasooriya, and to guarantee her safety,” IFJ General Secretary Aidan White said.

In July, the IFJ noted earlier threats made to the life of Balasooriya, who remains in Sri Lanka. Balasooriya lodged a complaint at a local police station, but by all accounts it was not acted upon.

Balasooriya has since shifted house for her own safety. However, on the evening of September 2 she had two unidentified visitors who spoke menacingly and vowed to find and kill Pushpakumara.

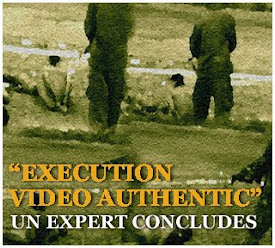

The two reportedly referred to Pushpakumara as a “traitor” and a “Sinhala Tiger” – in reference to the Tamil Tigers who were defeated in 2009 after a long civil war. He was accused of sending video footage and photographs of the last phases of the war to overseas media organisations with intent to entangle the Government of Sri Lanka in war crimes trials.

The threatening visitors accused Pushpakumara of acting in concert with General Sarath Fonseka, who was commander of the Sri Lankan army in the last phase of the war and challenged President Mahinda Rajapakse in presidential elections in January. Fonseka was arrested shortly after he lost the election in a polarised national vote, and recently stripped of his rank, pension and all benefits by a military court which found him guilty of conduct unbecoming.

Pushpakumara’s dismissal followed his leadership of a movement of SLRC staff demanding that prescribed norms on fair coverage for all candidates be followed by the state broadcaster, which was accused of tilting strongly toward the incumbent president.

The IFJ learns that Balasooriya has again complained to her local police station about the latest threats to her life, and encountered an uncooperative attitude from officials.

“The safety of Pushpakumara’s wife is a key indicator of the commitment of President Rajapakse’s regime, now invested with a fresh mandate, to restore the civil liberties that were seriously eroded during the civil war,” White said.

“Pushpakumara’s actions as a leader of the program producers’ association in SLRC were in line with prescribed norms of fairness in election coverage. Threats implying he was involved in the discovery of visual evidence of atrocities by Sri Lankan armed forces is consistent with a pattern of victimisation that began as retribution for his stand on a matter of professional ethics.”

© IFJ

Friday, September 10, 2010

Sri Lanka's constitutional amendment : Eighteenth time unlucky

The Economist

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

The Sri Lanka described in the revised charter is not a pretty place. It is one where the forms of parliamentary democracy are preserved but the substance has become subordinated to almost untrammelled presidential power. With the opposition divided, his rival in the presidential election in January in detention and his popularity still high, President Mahinda Rajapaksa already seems monarch of all he surveys.

The amendment changes the constitution in two main ways. The first is to remove the bar on the president’s serving more than two six-year terms. First elected president in 2005, and then re-elected with a thumping majority in January, Mr Rajapaksa has in fact not even started his second term. But he seems to be settling in for the long haul.

As government spokesmen have pointed out, however, Sri Lanka’s voters will at least have the chance to turf him out in six years’ time. That is why it is the second change that is more pernicious. It is (such is the way of descriptive constitutions) to overturn the 17th amendment. This was an admittedly muddled attempt to curb the powers of the “executive presidency”, partly through a “constitutional council”. After the latest change, the constitution will both grant the president immunity and also give him final authority over all appointments to the civil service, the judiciary and the police. He is also commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Almost the only formal constraint on him—electoral considerations aside—is an obligation to show up in parliament once a quarter.

Sri Lanka, goes the argument of Mr Rajapaksa’s cheerleaders, needs a strong executive to seize the chances of peaceful development offered by last year’s victory in the 26-year civil war with the Tamil Tigers. But confusingly they also point to that victory—grasped with a ruthlessness that shocked many of Sri Lanka’s foreign friends—as evidence of the virtues of a powerful presidency. Indeed, whatever problems Sri Lanka’s political system suffers from, the weakness of the presidency, which is already directly responsible for over 90 institutions, is not one of them. Quite the contrary: Mr Rajapaksa himself, before he tasted its benefits first-hand, used to campaign for the abolition of the executive presidency.

His new vision of further strengthening the president’s powers has been greeted with an outcry from Sri Lanka’s liberals, but few mass protests. The public must feel bewildered by it all. The change was pushed through as an “urgent” parliamentary bill in under two weeks from the draft’s first appearance, thanks to Mr Rajapaksa’s recent acquisition of the requisite two-thirds majority. Such important changes should have been put to a referendum. Mr Rajapaksa might well have won one. But a campaign would at least have thrown the issues open to public debate and scrutiny.

Because he can

The only urgent compulsions facing Mr Rajapaksa and his brothers (two have senior jobs in his government and a third is the parliament’s speaker) are those of parliamentary arithmetic and personal popularity. Still basking in the glow of military and electoral triumphs, the president has done in haste what he knows he can get away with. That he has preferred to put the consolidation of his family’s power ahead of a sorely needed national reconciliation with an aggrieved Tamil minority is a decision Sri Lanka will repent at leisure.

© The Economist

Friday, September 10, 2010

Sri Lanka to offer more oil exploration blocks

By Ranga Sirilal | Reuters

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

The Indian Ocean island's Petroleum Resources Development Secretariat said it was planning to call bids for blocks in 15,000 sq km of the shallow Cauvery Basin, just off the northern area the Tigers controlled until their defeat last year.

"A lot of Indian companies are showing their interest," Neil De Silva, director-general of the secretariat, told Reuters. "The depth there will be around 100 meters and the cost for explorations will be very low."

De Silva gave no details on how many blocks would be made available in the Cauvery basin, shared between India and Sri Lanka, which sits at India's southern tip.

American and Russian companies from the mid-1960s until 1984 did exploration work in the Cauvery basin, but no commercial oil was produced and the war's flare-up ended exploration.

Calgary-based Bengal Energy Ltd. (BNG.TO: Quote) has exploration rights for 1,362 sq km on the Indian side of the Cauvery basin, which already has nearly 30 operating wells.

Indian companies have already committed to exploring Sri Lanka's oil potential in the deeper Mannar basin, located further south along the western coast.

Cairn Lanka, a subsidiary of Cairn India , is due to begin drilling there by mid-2011 after completing a seismic survey. It has rights to 3,000 sq km. [nCOL372321]

Sri Lanka's government has said previous seismic data showed potential for more than 1 billion barrels of oil under the sea in a 30,000 sq km area of the Mannar Basin, located further south along the western coast.

Sri Lanka produces no oil and is totally dependent on imports, which cost it $2.2 billion in 2009.

© Reuters

This site is best viewed with firefox

Search

Is this evidence of 'war crimes' in Sri Lanka?

Archive

- ▼ 2010 (1312)

- ► 2011 (687)

Links

- Reporters Sans Frontières

- Media Legal Defence Initiative

- International Press Institute

- International News Safety Institute

- International Media Support

- International Freedom of Expression eXchange

- International Federation of Journalists

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Asian Human Rights Commission

- Amnesty International