Photo courtesy: Agron Dragaj

BBC Sinhala

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

R Thurairatnam, a member of the eastern provincial council (EPC) has written to the chief minister raising concerns of the move.

The central government, he says, is handing over nearly 20,000 acres in Batticaloa district exclusively among Sinhala nationals.

Lands of Ampara district to the north of Batticaloa and Polonnaruwa flanking its west have already been distributed, alleges Mr Thurairatnam.

"The lands belonging to the Mahaveli project, forestry department and tourist industry is being distributed in a manner biased to the Sinhala people," he told BBC Sinhala service.

Friday Forum

In a letter to Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan, the councillor has urged the chief minister to take immediate action to stop the "colonisation."

"When Tamil people trying to get a land, they are bound by the provincial land commissioner's regulations. But the provincial council was neither informed nor sought permission for this distribution," he added.

Members of the civil defence force are among the beneficiaries of the scheme, according to the councillor.

BBC Sandeshaya could not get the response of either of the land ministers in the government or the EPC despite repeated attempts.

The Friday Forum, headed by former UN diplomat Jayantha Dhanapala, has raised serious concerns over the “ad hoc manner” the government is trying to deal with land ownership in the north and east.

Releasing a discussion paper the Forum says the recent circular issued by the land ministry underlines “the importance of ensuring that property claims and access to land and housing in communities are accommodated with equity and fairness.”

© BBC Sinhala

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Alleged land colonisation in Sri Lanka's east

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Sri Lanka: Oppressed North - Lawless South

By Tisaranee Gunasekara | The Sunday Leader

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

"If they harm me, it is the country they harm,” Gotabhaya Rajapaksa | 'Daily Mirror' Hard Talk

In Sri Lanka’s one-family state, these triple despotic-roles have been appropriated by the Rajapaksa-troika: Mahinda Rajapaksa the sage-guide; Basil Rajapaksa the bountiful-provider and Gotabhaya Rajapaksa the vigilant-guardian.

The Nazis made out of Silent Night a children’s song hailing Hitler as the unsleeping-protector of the German nation: “…Only the Chancellor stays on guard; Germany’s future to watch and to ward; Guiding our nation aright” (Berlin at War – Roger Moorhouse). In a recent interview, (made quite revelatory by Shakuntala Perera’s searching questions) Gotabhaya Rajapaksa depicts himself as the sleepless-guardian of a feckless nation: “My primary concern is the security of this country. Maybe for the public and the politicians the concerns ended with the end of war but not for me. Day and night I work to prevent the LTTE from coming back… I work for the country – no one knows the work I do” (Daily Mirror – Hard Talk).

Officially, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa is just a senior bureaucrat. But, as his comments reveal, he is his brother’s de facto Defence Chief: “I have a huge task in re-orienting the war time military machinery to suit the peace times. I have to keep the forces active… I have immense pressure from the international community to reduce military presence in the NE….” (ibid). I, I, I; not even ‘The President and I’, but just I, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, the sole-protector of his family’s state.

Permissiveness and impunity are two key-ingredients of the Rajapaksa defence-doctrine. The consequent transformation of law-enforcement officers into vigilante-killers and Family-acolytes into criminal power-abusers is plunging the South into a state of lawlessness, as L’affaire Kolonnawa demonstrates. Rajapaksa maintains that Duminda Silva was not the monitoring MP of the Defence Ministry: “Defence Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapaksa….said that no Parliamentarian was appointed to monitor the activities of the Defence Ministry… Duminda Silva was entrusted with…supervising the…programme to build housing schemes…” (Daily News – 26.10.2011). The record shows otherwise: “President Mahinda Rajapaksa has appointed three Monitoring Members of Parliament. Sajin de Vass Gunawardena has been appointed as the Monitoring MP to the External Affairs Ministry while parliamentarians R. Duminda Silva and Uditha Sanjaya Lokubandara were appointed as Monitoring MPs to the Defence Ministry” (Ada Derana – 13.12.2010). The state-owned Daily News repeated the story, the next day. Incidentally this sensitive appointment was made while Duminda Silva was facing a charge of child rape!

According to Rajapaksa, Duminda Silva had “only 12 Ministerial Security Division personnel” (Daily News – 26.10.2011). His security-personnel “were given only two T56 weapons” (with which one of them reportedly shot Bharatha Lakshman Premachandra). So a junior parliamentarian with pronounced criminal tendencies was given ‘only’ 12 security-personnel and two T56 rifles! Are all junior parliamentarians treated so? How much security does a non-Rajapaksa minister get? Unknowingly, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa has bared the blatant favouritism which is a Rajapaksa-hallmark.

Reinventing the Vicious Circle

Gotabhaya Rajapaksa says he is eternally vigilant to prevent a Tiger-resurgence: “Although immediately after the war the morale of the LTTE died, over these past two years they started their funding and regrouping… If you sit doing nothing there is a huge threat. We are working very hard to counter this…” (ibid).

The LTTE did not come into being or grow into a world-class terror outfit in a vacuum. Without the Sinhala Only, the Tiger may have remained unborn. Without the Black July, the Tiger may not have grown exponentially. If the B-C Pact and the D-C Pact did not miscarry (thanks to the midwifery of Sinhala extremism), the LTTE, even if it was born, would have remained a fringe group.

The Tiger was born out of Tamil discontent and alienation; it fed on Tamil fear and anger. A policy of preventing a Tiger-resurgence needs to take this history into account. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa may be labouring day and night to prevent a Tiger-resurgence. But the militaristic approach and Sinhala supremacist policies of the Family cannot but fan those old-embers of Tamil fear and ire into new-life.

When a sober, anti-Tiger Tamil leader like V. Anandasangaree says the current plight of Tamils makes him question the purpose of his living, it is an omen of a calamity-in-the-making. The particular event which caused this despairing outburst was the expropriation by the Air Force of “an 8,000 acre area between Pudukudurippu and Nandikadal in Mullaitivu…” (Sri Lanka Mirror – 19.10.2011). This is not an isolated incident. In the North/East, civilian lands are being appropriated to build new bases for the forces and cantonments for their families. According to parliamentarian M. A. Sumathiran, “…Tamil people inhabited 18,880 sq km of land in the North and East, but after May 2009, the defence forces have occupied more than 7,000 sq km of land owned by Tamil people” (Transcurrents – 23.10.2011). The new Bill which empowers the state to expropriate assets it deems ‘underperforming and underutilised’ can exacerbate this situation.

The omnipotent and omnipresent military intrudes into every aspect of Tamil-life. Not only must the army be informed about visitors. “Any family gathering to celebrate the birth or naming of a child, attainment of puberty of a girl, a wedding or even a death, requires prior permission… The army must be informed even of community activities such as sports meets. In a recent incident in Chavakachcheri, youth participating in a football match were brutally assaulted by the army as they had played on a field without the permission of the army… It is common to see the presence of soldiers in all civilian activities including village, temple or church meetings” (ibid).

What if a Sinhala village is forced to obtain permission from a predominantly Tamil army for most acts of daily life? Would not such humiliation cause fury and rebellion? The Rajapaksas are using targeted-attacks to prevent Tamils from protesting against the insults and oppression which are their daily fare. The recent assaults on two student-activists of the Jaffna University follow the brutal attack on the news editor of Uthayan. Sustaining this military-domination would require the defence budget to remain at stratospheric-levels, despite escalating financial difficulties.

The Rajapaksa’s Northern policy combines ubiquitous military presence with demographic re-engineering. Military cantonments represent a novel form of state-managed colonisation of traditional Tamil areas. These enclaves would need support services, enabling the military to further encroach into civilian-areas, such as education. The children of military-families will need Sinhala schools and who better to run them than the military?

As relatively privileged and empowered oases, these Sinhala enclaves will be the locus of Tamil resentment. This seems a replication of the Israel strategy of breaking the contiguity of Palestinian-presence through the creation of Jewish-settlements. That policy is obstructing a sustainable-peace, compelling Palestinians and Israelis to languish in a state of fear and insecurity. This may be the destination the Rajapaksas want for Sri Lanka. Frightened people are more likely to barter liberty for security and that is a state made for despotism.

© The Sunday Leader

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Sri Lank's war displaced: Despair and destitute

By Namini Wijedasa | Lakbima News

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

Kalachelvi says she is 36-years-old. She has two other children, 11-year-old Yasinthan and six-year-old Hariharan. Her hair is plaited and twisted into knots on either side of her head – almost like LTTE women soldiers used to wear it. She makes no secret of their former connections to the Tigers. What does it matter now?

Kalachelvi’s husband once fought alongside the Tigers but as the battle became bloodier, she says, he abandoned them for his family. They chose to stay in the Wanni even as troops advanced. “We just moved, moved, moved and ended up at Mullivaikkal,” Kalachelvi recounts.

There, corralled in with hundreds of thousands of others, they waited. One day, in May 2009, her husband told her he would go for food. He asked her to get drinking water. They left the three children sitting side by side. Kalachelvi returned with water to find her husband and Kirubalini gone. Nobody knew where they were.

As the war intensified, they fled the Wanni and lived in Menik farm for two years. Kalachelvi begged for news of her husband and daughter–from UNHCR, ICRC, from officials, the army, and the newspapers. Nothing came up.

She may have left everything in the Wanni but like many others who ran from the fighting, Kalachelvi took her photos everywhere. For those with missing family members, these are now their most treasured possessions. She gave one image to the Department of Childcare and Probation which had it published in a newspaper.

In the meantime, they moved out of Menik Farm and settled in the Wanni although not in her original village. She can’t go back because her in-laws blame her for the loss of their son. Besides, they were once a comfortably-off “LTTE family” that had pulled rank on others. With the war over and the Tigers gone, they were ostracized because of it.

Kalachelvi later heard of the Family Tracing Unit (FTR)–a joint venture between UNICEF, the Vavuniya Divisional Secretariat and the Department of Childcare and Probation–and trekked to its office at the kachcheri with her photos. Since December 2009, it has received 690 complaints of missing children. They took down her details, scanned her daughter’s image for their database and sent her home.

Found and lost

Some months later, a lady from FTR called her mobile phone–an incongruous instrument seen in every home we visited however destitute its residents might be. “I went,” Kalachelvi said. “They didn’t show my daughter but they showed me a computer with a lot of photos.”She recognized Kirbulani instantly when her image sprang up on the screen.

The child, now around eight-years-old, was traced by the FTR to a children’s home. They matched her with the family to the extent possible and arranged a visit. But when Kalachelvi met her daughter for the first time, accompanied by childcare and probation officers, the girl did not recognize her mother.

Kalachelvi suddenly fell at our feet, worshipping us and wailing. She beat her chest and cried agonisingly that she wanted her daughter back, her little ammachchi. But the case is far from closed. Childcare and probation officers are counselling mother and daughter to recreate the ties they once had. For the moment, Kirubalini shows no inclination to rejoin her mother. It also remains unclear how she lost recollection of her.

Protection officers are concerned about the circumstances Kalachelvi lives in. She does not own a home and her two sons are not in school. They need clothes, books, shoes. They are badly dressed, dirty and desperately poor.

“I was told I would get a house somewhere because I’m living on somebody else’s land,” Kalachelvi sniffed. “I’m doing roadwork and I think they put my money in the bank. I also get food rations and my relocation allowance is also in the bank...”

“It isn’t enough to trace the children and to establish a connection,” explained Manaru Deen, a UNICEF protection officer. “Probation and childcare officers must be satisfied that the child will be returned to a good, safe environment. They have to assess the financial situation, whether the child will have food and clothes when she returns. The courts will make a directive.”

Flies alighted on three cooking pots containing meagre portions of food. A sheet of plywood affixed to a wall served as a shelf. It held a small bottle of talc, a hair clip, a mirror and coconut oil. Kalachelvi quietly stroked the face on the computer printout.

“I will go from here when my husband comes back,” she said. “The soothsayers say he is alive. They said the same about my daughter.”

A shattered childhood

It was dark when we reached the Vavuniya home of nine-year-old Rajeswaran Vidushan. The light of a bottle lamp fell on his twisted right leg. “Shell,” he said, when asked what had happened. The boy speaks mostly in monosyllables. His story is disjointed, sometimes incoherent. Often he just stares at you blankly.

He says he was playing with his older sister at Muttiyankatti during the end of the war when a shell landed on them. His sister, grandfather and grandmother were killed. Vidushan was grievously injured. He can’t remember the details of what happened next.

Vidushan was a Grade One student when all this happened. His sister was in Grade Three. The schools were closed because of fighting and they (Vidushan, his sister, grandmother and grandfather) were displaced “many times.” His father had abandoned the family early on. His mother was earning a living abroad. “Foreign country,” Vidushan replies, when asked where she is.

One of the boy’s cousins said Vidushan was taken by ship from Mullaitivu to the hospital at Pulmoddai where Indian doctors tended to him. He was later transferred to the Vavuniya hospital and his family lost track of him. Nobody knew which hospital he was at or whether, indeed, he was dead or alive.

In the meantime, his mother returned and started the searching for Vidushan. After seeing an advertisement about family tracing, she gave his details and a photograph to the FTR. The Probation and Childcare Department advertised his picture in a newspaper but nobody came forward. It was some weeks before the FTR stumbled upon the case of a child who was treated at Pulmoddai, transferred to Vavuniya and who now lived in an institution. Mother and son were soon reunited after their case was processed by the court.

A month later, Vidushan’s mother left him in the care of his aunt and went abroad again. He also has a sister in a children’s home in Mannar. His aunt is a farm labourer. “I worked a lot today, my back really aches,” she said.

Vidushan is permanently disabled and visits the clinic regularly. His leg is bent at an odd angle. Yet he walks two kilometres to school if the bus doesn’t come. He likes Tamil and mathematics. “Doctor,” he grins, when asked what he wants to be. His mother will come “in March,” he says repeatedly. Their time together had been painfully short.

Still missing

A rooster pecked about in 49-year-old Shanthakumar Kamala’s yard at Semamadu in Vavuniya. It was early morning. Her husband, Thurairasa, was away at work but her son, Thanuthasan, was home. He was recruited forcibly by the LTTE in 2008 but ran away to Vavuniya soon after. The police detained him and he spent ten months in jail before being released. He still attends court.

Thanuthasan had just finished his A/Levels when he was conscripted. “I was twenty-one,” he says. “I dropped out of school for one or two years to avoid recruitment,” he recounted.

In the meantime, Kamala and her family fled deeper into the Wanni as troops closed in on the LTTE. They stumbled from Kanakarayankulam to Muttayankattu; from Puthukuduyirippu to Iranapalai; and from Thevipuram to Irattavaikkal.

With them was 16-year-old Thanuraj, the youngest son. On 26 February 2009, he was sleeping inside a bunker when they came for him. “The LTTE came in a pickup,” Kamala said. “The bunker was close to the road. We couldn’t hide him. I pleaded with them. I told them he was only 16. They said his age didn’t matter. They insisted that someone must join them from each home.”

The cadres told her to come to their camp later. She could speak to their commander and if he said Thanuraj could go they would release him. She tried it but did not succeed. Instead, they gave her a poralai card–a fighter’s card–to certify that her family had given up one member and did not need to offer another.

It was the last she saw of Thanuraj. They were displaced again within five days of his conscription. She can’t remember the name of the village but says they were on the beach. She started hunting for her son, joined by another woman whose 17-year-old daughter was also forcibly recruited. This girl escaped from the LTTE just before the war ended and rejoined her family.

In March, Kamala’s husband was shot in the arm and LTTE gave him tablets. “Bullets came from every direction,” she said. “There was heavy fighting.” In April, she joined droves of desperate people to flee the Wanni, taking the Vattuvaikkal Bridge over the Nanthikadal lagoon. Asked why she didn’t leave the area earlier, she says the LTTE would not let them. “They wouldn’t give us passes,” she explained. “They kept telling us to move inside.”

“I saw bodies in the water before I fainted,” Kamala said. “I don’t know how many but others say there were lots.” After spending one night at Omanthai, they joined hundreds of people on a bus to Menik Farm. She resumed the search for Thanuraj, lodging appeals everywhere.

In January 2010, Kamala gave his details to the FTR. They haven’t been able to trace him. “They are checking in their computer but there is no match,” Kamala sobbed. Thanuthasan swatted at flies. The smell of cow dung, smeared on their clay walls to ward off termites, is strong. There are beetroot peels on the floor.

“I wasn’t there during the last days but I believe he is somewhere,” Kamala says, bringing out photos of a smart young man in school uniform and in Boy Scout’s garb. They too were well-off once. They owned seven acres of paddy land, a house, a tractor and two cars.

Now they would be happy just to get their son back.

FTU trying to locate those missing

Hundreds of family members were separated from each other at the height of the war in 2009. Vavuniya Government Agent Mrs. P.S.M. Charles spearheaded an effort within the camps at Menik Farm to reunite people. But probation and childcare authorities continued to receive complaints of missing children. In December 2009, the Family Tracing Unit (FTU) was opened at the Divisional Secretariat with UNICEF support. Up to September 2011, it received 690 applications from families looking for missing children, said Brig. J.B. Galgamuwa, the head. Of these, 490 were conscripted by the LTTE. The unit has currently matched 113 names from their database to the applications. Of these, 29 children have already been physically handed over to the parents. A number of other applications are being processed.

© Lakbima News

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Living on a dollar a day in a “middle income nation”

UN Regional Information Centre

.............................................................................................................................................................................................

"People ask why they should help a middle-income country; what they fail to see is that there are large pockets of poverty here," Andre Krummacher, the ACTED country director for Sri Lanka told IRIN, the news service of the UN Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Others have blamed the international focus on alleged war crimes committed during the last phase of Sri Lanka's war and moves to initiate an international investigation as distracting donors.

"There has been so much attention on this that donors seem to have lost sight of the conditions in the former war area," Jagath Abeysinghe, president of the Sri Lanka Red Cross Society.

UN Officials indicate it is highly unlikely the full appeal would be met this year. Further constraints were avoided in May this year when Valerie Amos, UN Emergency Relief Coordinator, released $4.9 million to the priority sectors: food security, agriculture, protection, shelter, water and sanitation, nutrition and health.

The UN World Food Programme (WFP) office, whose emergency food assistance is funded through the JPA, said it had not limited or suspended food distribution due to funding constraints and that food intake in the province was still acceptable - albeit deteriorating.

"Over 60 percent of households in the Northern Province are food-insecure, and lack the income generation and food-production capacity to secure basic needs," the WFP told IRIN.

The latest WFP assessment found that half the households in the Northern Province lived on less than $1 a day. According to the UN's latest Joint Humanitarian and Early Recovery Update, released on 24 June 2011, 63 percent of returnees live below the poverty line.

"The reality is that there is food, but it is very expensive, people don't have the income to buy it," said Andre Krummacher, ACTED country director for Sri Lanka. He said the impact of tight budgets and insufficient job opportunities was becoming apparent: "Soon we will see more unless the tide changes," he said.

© UNRIC

This site is best viewed with firefox

Search

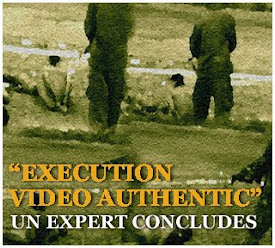

Is this evidence of 'war crimes' in Sri Lanka?

Archive

- ► 2010 (1312)

- ▼ 2011 (687)

Links

- Reporters Sans Frontières

- Media Legal Defence Initiative

- International Press Institute

- International News Safety Institute

- International Media Support

- International Freedom of Expression eXchange

- International Federation of Journalists

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Asian Human Rights Commission

- Amnesty International